I have been thinking a lot about second novels. I sent my own to the publisher a few weeks ago, and since it won’t be released until March, I have plenty of time to wonder (and worry) about what just kind of novel I wound up writing.1 Is it something people will look back on as “a transitional McDade novel,” or a large step forward (or backward) from the promise of The Weight of Sound?2 I didn’t think in those terms while writing, which is for the best; I find finishing a book is only enjoyable, never mind possible, if I do not think about anything except the characters. Even the themes are something I am not fully aware of until I am in the final revisions.

I will note, however, that no one sets out to write a “transitional novel.”

Knowing full well that to compare is to despair, I still went ahead and looked for lists of famous second novels, and found plenty of reasons to be intimidated—I may not have written 100 Years of Solitude or Pride and Prejudice, perhaps.3 Then I reassured myself by remembering that my favorite second novels tend to be a bit shaggy. Stretches of brilliance mingle with stretches where things sort-of-almost go off the rails, as if the author had been given a goose that laid golden eggs but wanted to see if the same goose could be taught any new cool tricks, like pole vaulting or biscuit making.

I was going to write a blog post celebrating those kinds of second novels, but found that someone had already published a decent version of what I had in mind.4 So I decided the best way to stop obsessing over the fate of my yet-unreleased book was to revisit some second albums I have loved, to see what lessons could be learned. Most of them fell into one of three categories: Repeat and Play, the Great Leap Forward, and the Ambitious Mess. As with any good attempt to create impossible categories, I will make my claims loudly and definitively, and then eagerly wait to see how many people can prove me wrong.

Repeat and Play

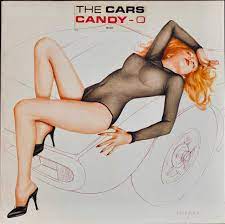

The first two records by the Cars look similar visually, both covers featuring a woman with her right forearm draped over her forehead; the only difference is that on the second album she is no longer driving the car, she is waiting for you on top of the hood, eyes shut.5 Even the lyric sheets are formatted in the same style, running left to right in a straight, non-poetic presentation, with “i” instead of “I.” The songs on Candy-O follow the same basic formula as they did on the debut: Ric Ocasek sings the weirder ones, Ben Orr sings the more traditional singles, and the most interesting musical textures coming from Elliot Easton’s guitar riffs. Most impressive of all, the two records are almost exactly the same length: 35 minutes for the first, 36 minutes for the second.

Don’t get me wrong: I am not dismissing Candy-O as a mere copy. As a teen, I loved both records, and found the similarities, visually and musically, very satisfying. From my vantage point now, I can also appreciate how hard it is to create something that follows the same formula but also succeeds. It’s a compliment to say that when I listened to the two albums back to back, while writing this, it felt like one long record. And we should also remember that they were made in an era where bands were expected to put out albums every year: only fifty-three weeks separates the two records. If The Cars came out now, I imagine the record label would milk it for several years, with singles and multiple tours, allowing the band to have several years to work on their follow-up.

As much as I tried not to be too aware of my approach while working on the second novel, I was consciously trying to avoid writing First Novel 2.0. I was curious to see where the characters of the first book went next, but was also determined not to follow them, and abandoned an earlier attempt at the Next Book when it drifted too close to the same territory as the first. I even vowed not to have a musical soundtrack, to prove how different this new one would be, but, well, that changed pretty early in the writing.6

The Great Leap Forward

I should confess that I’m a guy who has happily stood in the pit at a Radiohead show for two or three hours before the band even starts, just so I can get as close to the source as possible.7 Their first album, though, only hints at what they would achieve with their second. Pablo Honey has the right pieces—walls of guitars, playing with offbeat and syncopated rhythms, and, of course, Thom Yorke screaming into the universe—but most of the songs themselves sound incomplete, and tend to end too quickly or ramble on for too long. It’s like the band found a box of cool toys but didn’t really know how to use them until The Bends. I had been so unimpressed with Pablo that I didn’t even know the next one had been released until one of our roadies insisted it was much better, and worth a listen. (Thank you, Steve, wherever you are.)

Taking a Great Leap Forward with the second record doesn’t necessarily mean the first was bad, either. Elvis Costello and Neil Young both found their perfect bands the second time around; while their debuts are both good, This Year’s Model and Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere are much more intense and exhilarating listens, driven by the thrill of songwriters finding a way to achieve the sounds inside their heads.

Let’s face it: every author wants to write a book that will be viewed as A Great Leap Forward. I did not have access to any new tools with the second novel, though; still just me and a laptop and whatever’s in my head. I’m not sure how possible Leaps are for me, but maybe you don’t realize you can do it until you’ve done it?

The Ambitious Mess

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1606410-1553943084-3314.jpeg.jpg)

I’m unable to quantify how much I loved (and still love) the first Pretenders record. I remember putting the needle down and being equally scared and thrilled by “Precious,” then confused by everything about “The Phone Call” (wait, you have to count seven?). Halfway through the third track, “Up the Neck,” I decided this was one of the best albums I’d ever heard.

Pretenders II isn’t as good, and there are those who would put this in my first category. It’s certainly similar in approach and structure (eleven Chrissie Hynde songs, and hey, another one by Ray Davies!), but I put it firmly in the Ambitious Mess category. I mean, no one will include “Bad Boys Get Spanked” on their list of Hynde’s best songs, but the driving groove is hypnotic, and the whip noises and over-the-top Hynde growlings make it almost as an odd choice for second track as “The Phone Call.” In fact, the entire sequencing of II has always fascinated me. Starting with “The Adultress” and “Bad Boys” seemed like an odd choice, and then placing two slow songs, both in 6/8, back-to-back? Just sloppy, or stoned, or making some kind of statement?

At the same time, “Message of Love” and “Talk of the Town” are two very different sounding, but equally glistening, singles.8 And while there are moments the band really seems to phone it in (listen to “Pack It Up” again, if you need evidence), there are also some songs on side two that hinted at interesting places this line-up could have gone next if half the band hadn’t overdosed on heroin. Call me crazy, but I love “Day After Day” and “English Roses,” two expertly constructed and performed pop songs, and the hyperactive bass line and horns of “Louie Louie” that close the album sound like a young band running a victory lap, blowing off some steam before they get back to work and make something even better, all capped off by Hynde’s final shout of “Let’s Go!”

We All Transition In The End

I certainly didn’t set out to write a shaggy mess of a novel, any more than I set out to replicate as much as I could from the first one. I also don’t think I figured out some magical way to make a Great Leap Forward. What is interesting to me looking over my (admittedly random) list of examples now, though, is that all these second records were, in the end, transitions. The Cars went on to make Panorama, an odd creation that would certainly be in the Shaggy Mess category, while Radiohead took another giant leap, this time straight into their more electronic period with OK Computer. The Pretenders were forced to transition by tragedy, but Learning to Crawl is a more polished creation

Which means that my second novel, whatever the world thinks of it, is destined to mark some sort of transition as well. I suppose that is something best embraced, instead of worried about. Better to be keep making stuff and keep moving, be it forwards or backwards or sideways.

Notes

1 This does not mean the book is “done,” since I will still have to obsessively check the galley for miscues, and proof the audiobook, and lots of other things. Done in the writing world means “as done as the universe will allow.”

2 You know, people! Like, people running seminars on the meaning of the hi-hat in McDade’s novels, or the subtext of the lyrics “Bannister.”

3 Note: no one sets out to peak with their second novel, not even Gabriel García Márquez.

4 See: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-caw-off-the-shelf3-2009may03-story.html. The article did not mention my own favorite shaggy second novel, John Henry Days by Colson Whitehead.

5 OK, now I need someone to write an academic article on the agency, or lack thereof, of women on the album covers of the Cars.

6 I did take a different approach to the creation of the soundtrack this time, which is something I’ll probably ramble about in some future blog post.

7 And yes, I’m one of those annoying fans who insists their favorite band is best experienced live. In this case, I find the music much more human, much warmer, when performed live—especially the “beepy” stuff. If we need to able to accept the imperfections of the things we love, well, I confess that the band’s records are sometimes too carefully assembled.

8 As true addicts, I remember my friends and I being disappointed that these were included, since we’d already purchased the EP with both singles on it.